Features:

Journalism lost its culture of sharing

Here’s how we rebuild it

Attendees at the News Product Alliance Summit in October 2025 (Andrew Weeks Photography)

If you’ve worked in a technical role in news for long enough, you likely remember when the “show your work” spirit was everywhere. Newsroom nerds shared code on GitHub, swapped tips on social media and unfurled long blogs guiding others on how to get things done.

You might also have a vague sense that — like reaction GIFs, demotivational posters and that guy who sang “Chocolate Rain” — you’re seeing less of it these days.

We crunched the numbers, and your hunch is right. In fact, it’s probably worse than you think. The data are clear: The open-source culture that defined an earlier era of online journalism has collapsed.

Activity on GitHub has cratered. In 2016, news organizations posted more than 2,000 public projects to the code-sharing site. Last year, that number slumped below 400, an 80% decline.

It’s not just code. Posts to the NICAR-L listserv, once a mandatory part of every data journalist’s diet, are down 89% from their peak.

Some of the drop can be explained by the journalism industry’s well-reported recession. A decade ago, Buzzfeed News, Mic and FiveThirtyEight were among the most prolific newsrooms on GitHub. Today, they’re either closed or struggling to stay afloat.

But it’s about more than money. Organizations that flourished online also walked away. At its peak, The New York Times released dozens of public repositories on GitHub each year. In 2024, it posted zero.

It’s not all bad news. A small crop of startups, non-profits and other non-traditional news organizations stepped up. Groups like The Pudding, City Bureau and Bellingcat have pioneered promising new models built on openness, organizing and inspiration. Unfortunately, their success is overshadowed by the dramatic declines elsewhere.

As believers in the importance of openness to innovation, we wanted to understand why the movement stalled — and what could be done to revive it.

So we interviewed more than a dozen leaders from newsrooms of all shapes and sizes, covering those that slowed, those that sped up, and those that stopped entirely.

Their explanations revealed the economic, technological and institutional changes that have pushed even the most inventive organizations to retreat.

Our findings served as the starting point for a discussion at the News Product Alliance summit in Chicago. Dozens of news professionals gathered to debate how to reverse the trend.

Together, we generated ideas that offer a hopeful path forward. Unlike many of the problems facing journalism, this one seems solvable. It won’t require revolutionary new business models or massive funding from foundations or the government — just a clear-eyed look at why we lost a valuable habit.

Why sharing matters

To understand what’s been lost, we need to look at what once was.

From the early days of the Internet, news organizations created transformative technologies that shaped how the web works.

In 2003, developers at the Lawrence Journal-World in Kansas created Django, a Python web framework built to handle the demands of a local newspaper moving online. It became one of the most popular web frameworks in the world, ultimately powering the first version of Instagram and many other important websites. Fellow innovators at The New York Times, NPR, The Guardian and Norway’s Verdens Gang invented other open-source tools that revolutionized content management, data analysis and interactive storytelling.

At ProPublica, teams published detailed white papers alongside major investigations, explaining their quantitative methodologies with scientific rigor, allowing other researchers to verify and learn from their work. Major news organizations ran active blogs where they shared techniques and lessons learned. Conference presentations at NICAR and elsewhere became venues for passing along hard-won knowledge.

This culture made newsrooms more attractive places to work for civic-minded technologists. If you had programming skills and wanted to use them to make a difference, journalism offered you the chance to build things that mattered and share them with the world.

The approach also helped news organizations evolve to survive on a difficult digital frontier. It is needed now more than ever as artificial intelligence is poised to change how people access information, how they decide what to trust and how they understand the world.

“We are probably at the precipice of the biggest technology revolution of my whole career, and I’ve been doing this since 1997,” said one attendee at the NPA Summit, “This is a time when we most should be sharing with each other.”

This isn’t all just theoretical to us. We are indebted to the generosity of people who helped us get started in our careers by giving us code or explaining how something worked. If it weren’t for openness in news, neither of us would be writing this. There’s a fair chance that the same is true for some of you.

How did we get here?

From our conversations, three patterns emerged:

1. Economic collapse

The most intuitive explanation is economic: that many organizations either lost technical staff or, in the worst cases, went entirely extinct.

“The biggest barrier is just that FiveThirtyEight is not there anymore,” said Dhrumil Mehta, a former staffer who now teaches at Columbia and Harvard.

Journalism’s contraction put pressure on even those who survived.

“When the rest of the news industry is being squeezed, it provides you with some job security to keep all your secrets,” Jan Diehm of The Pudding said. “If your skills are locked away, it can ensure there will be a place for you and your craft.”

Where the will to share still exists, the resources to do it are often gone.

“People are tightening up all across the economy,” said E.J. Fox, a freelance consultant who used to work at NBC News. “People are careful with their time and energy.”

But economics alone are insufficient to explain the shift. Many rich and well-resourced organizations have stepped back, while some small, cash-strapped operations have stepped up.

2. Technological maturity

Another explanation we heard was that many of the problems that incentivized innovation have been solved. Good software, often free, is available. There’s less need to build something new.

“The decline might actually be a sign of success,” said Aron Pilhofer, who led teams at The New York Times and The Guardian. “We don’t need 18 different frameworks. Svelte exists in the world. D3 exists in the world.”

Andrew Kuklewicz of PRX made a similar point.

“For almost every gem or library or npm module, there are five of them that do what I need,” he said.

The rise of commercial vendors offering polished solutions for common needs, from data visualization to content management, reduced the pressure to build and share custom tools.

“Datawrapper is really good,” said Pilhofer. “You have to ask, ‘Why would you not use Datawrapper?’”

And when tech giants like Google and Facebook entered the space with tools like Angular and React, news developers found it harder — and sometimes unnecessary — to compete.

Kuklewicz sees new opportunities emerging at the dawn of AI.

“It is another kind of Cambrian explosion,” he said. “AI has opened a whole new green field for people to go max out on.”

And even as new problems emerge, plenty of old problems still remain. Our ongoing struggles with building sustainable businesses and loyal audiences are bigger than any single organization, and would benefit from shared lessons and collaborative solutions, our interview subjects said.

3. An inward shift

The most successful news companies grew their technical teams and better integrated them into the organization, making it less necessary for staffers to find community among colleagues elsewhere.

“You pushed further and further into the center of the newsroom and became more inward-facing and less outward-facing,” said Paul Bradshaw, who teaches at Birmingham City University and runs the Online Journalism Blog.

The professionalization of these teams also changed their leadership, evaluation criteria and incentives, making them more like Silicon Valley technology companies.

“Open-sourcing code doesn’t contribute to sprint goals or quarterly objectives,” said Tiff Fehr, who worked at The New York Times more than a decade before starting the consultancy Gasworks Data. “You’re driving agile processing cycles. You’re meeting your OKRs.”

One coder who asked to remain anonymous put it this way: “If leadership doesn’t care about it, and it doesn’t help you get promoted or get you more money or get you more respect in the newsroom, people just don’t do it.”

And for many industry veterans, personal circumstances changed as they’ve gotten older. They have families and less time to contribute. One developer with a young family told us that the grind of responding to GitHub issues and pull requests, even for projects he cares deeply about, has become hard to sustain.

Finally, once robust channels for sharing have declined or become walled gardens. Twitter all but disappeared as a space for news nerds to share work and ask questions. NICAR-L became less central as the community fragmented. Private Slack workspaces replaced open forums, creating smaller, more isolated circles of conversation.

How to fix it

The slippery slope of decline is not inevitable. At the NPA Summit and other industry conferences, participants presented what they’re building. The American Journalism Project’s OpenAI grantees have been posting their work to GitHub. The infrastructure for collaboration still exists. What’s missing is the culture and incentives to use it.

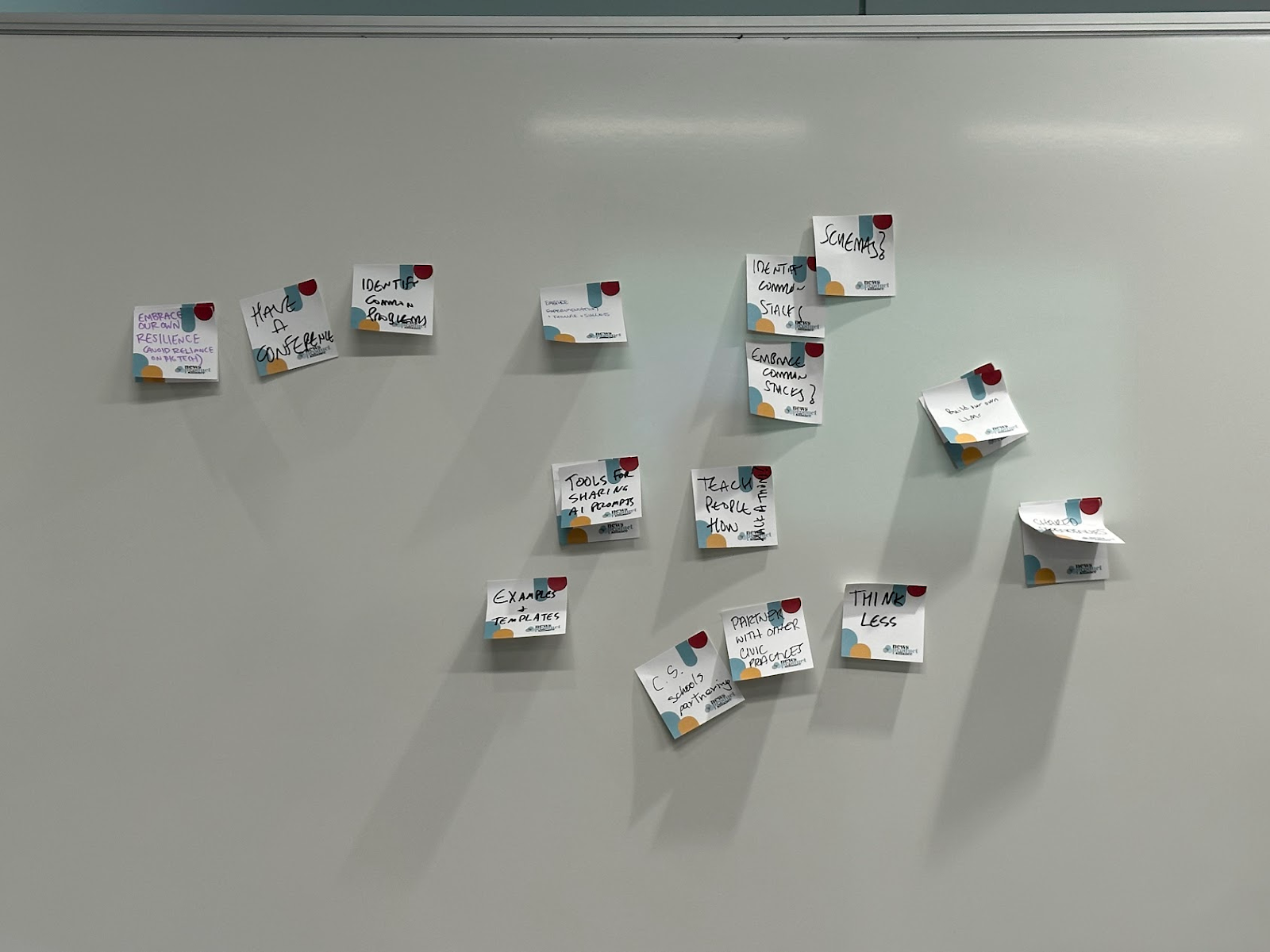

At the NPA Summit, we asked the room to help us think through solutions. We formed groups and collected ideas on sticky notes. Combined with ideas from our interviews, some patterns emerged.

What an individual can do

Participate in other people’s projects.

Filing issues, improving documentation and submitting pull requests to existing repositories helps build the ecosystem. It’s easier to join a conversation than to start one.

“Nobody goes to an empty restaurant,” Derek Willis said.

Share your AI experiments.

Publishing your prompts, Custom GPTs, and other experiments can help others learn faster – even when they don’t involve code at all. Sahan Journal and Centro de Periodismo Investigativo both released Custom GPTs last year.

Write “how I did this project” posts.

The Pudding’s approach of developing work in the open and including methodology sections with every project offers a model that doesn’t require maintaining complex software libraries.

Integrate open-source skills into your journalism classes

Dhrumil Mehta’s students at Columbia build portfolios through their GitHub contributions, creating work that future employers can see and evaluate.

What a newsroom can do

Assign someone to coordinate

Several people suggested creating dedicated roles. The idea of an “Open-Source Editor,” someone whose job is to help teams package and release their work, came up repeatedly at the NPA session.

Make it count

Making contributions count toward promotions and career advancement would align individual incentives with the collective benefit.

“It would help if you literally made it part of like people’s responsibilities,” Willis said. “We expect you to devote some amount of time to releasing.”

That also includes how potential hires are evaluated. PRX asks about GitHub repositories and contributions during hiring, identifying people who are already excited about working in the open.

What the industry can do

Recognize it with awards

Multiple people suggested awards and recognition programs for outstanding open-source work. As one developer told us, prizes and public recognition would help align contributions with career goals.

Create space for collaboration

Add session time at conferences for hackathons and practical discussions about what we’ve learned and where we’re stuck.

“We need a venue for problem sharing,” said Pilhofer. “Even if we didn’t fix any of them, just cataloging them” would help organizations see where collaboration might be valuable.

Help nonprofit grantees release their code effectively

While many institutional funders have open-source requirements in grant agreements, resources are needed to make sure that code is easy to reuse, and widely adopted.

–

The code and data used to produce this analysis are available on GitHub. Follow @openjournalism.bsky.social to be notified whenever a news organization releases code.

Credits

-

Scott Klein

Scott Klein

Scott is an entrepreneur in residence at Newspack, helping publishers on WordPress and other platforms do great election coverage by building and adopting innovative tools and by working together. He was previously at ProPublica and at THE CITY. He’s also on the board of Muckrock. Scott is based in Brooklyn, New York. Scott is also co-founder of DocumentCloud, a two-time recipient of the Knight News Challenge. DocumentCloud is a service that helps news organizations search, manage and present their source documents.

-

Ben Welsh

I’m an Iowan living in New York City. I work as a reporter, an editor and a computer programmer. My job is to use those skills, together, to find and tell stories.

Journalism lost its culture of sharing

Journalism lost its culture of sharing